- Types of Sailboats

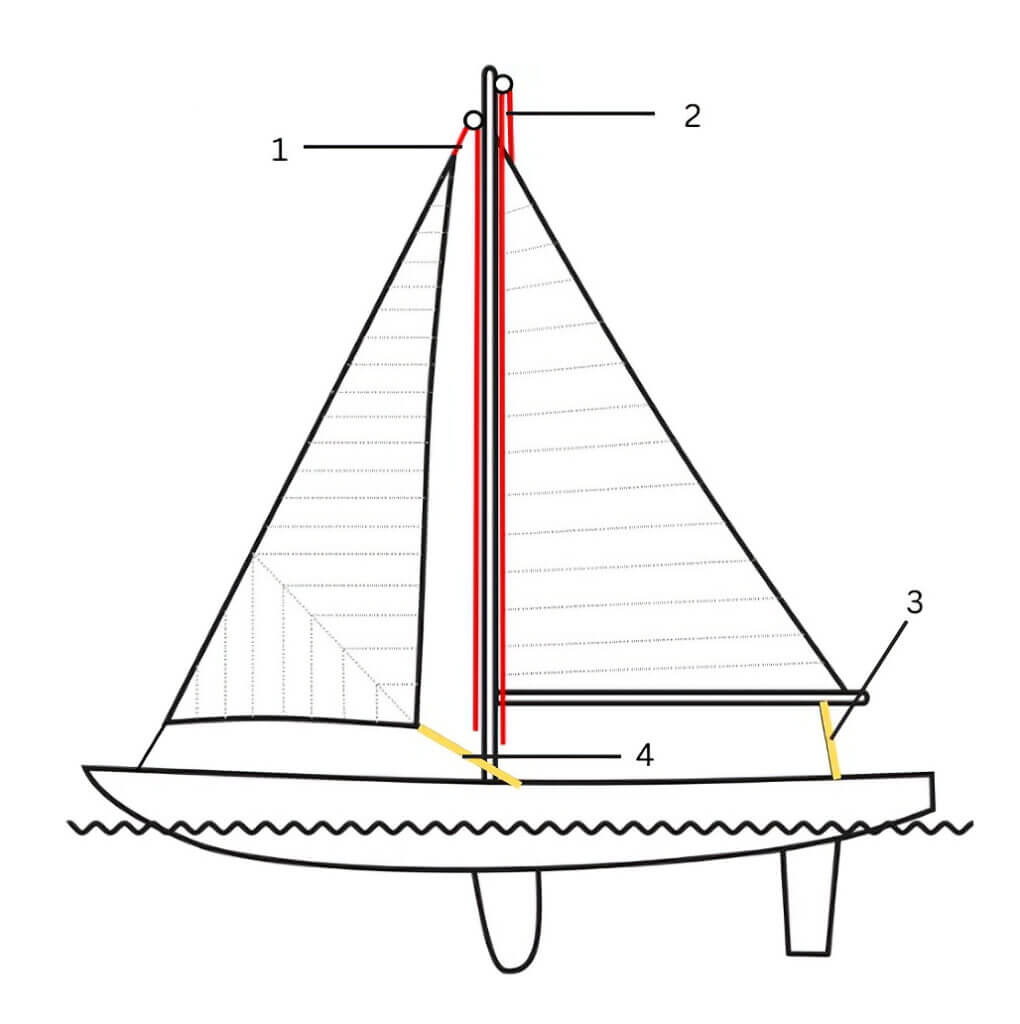

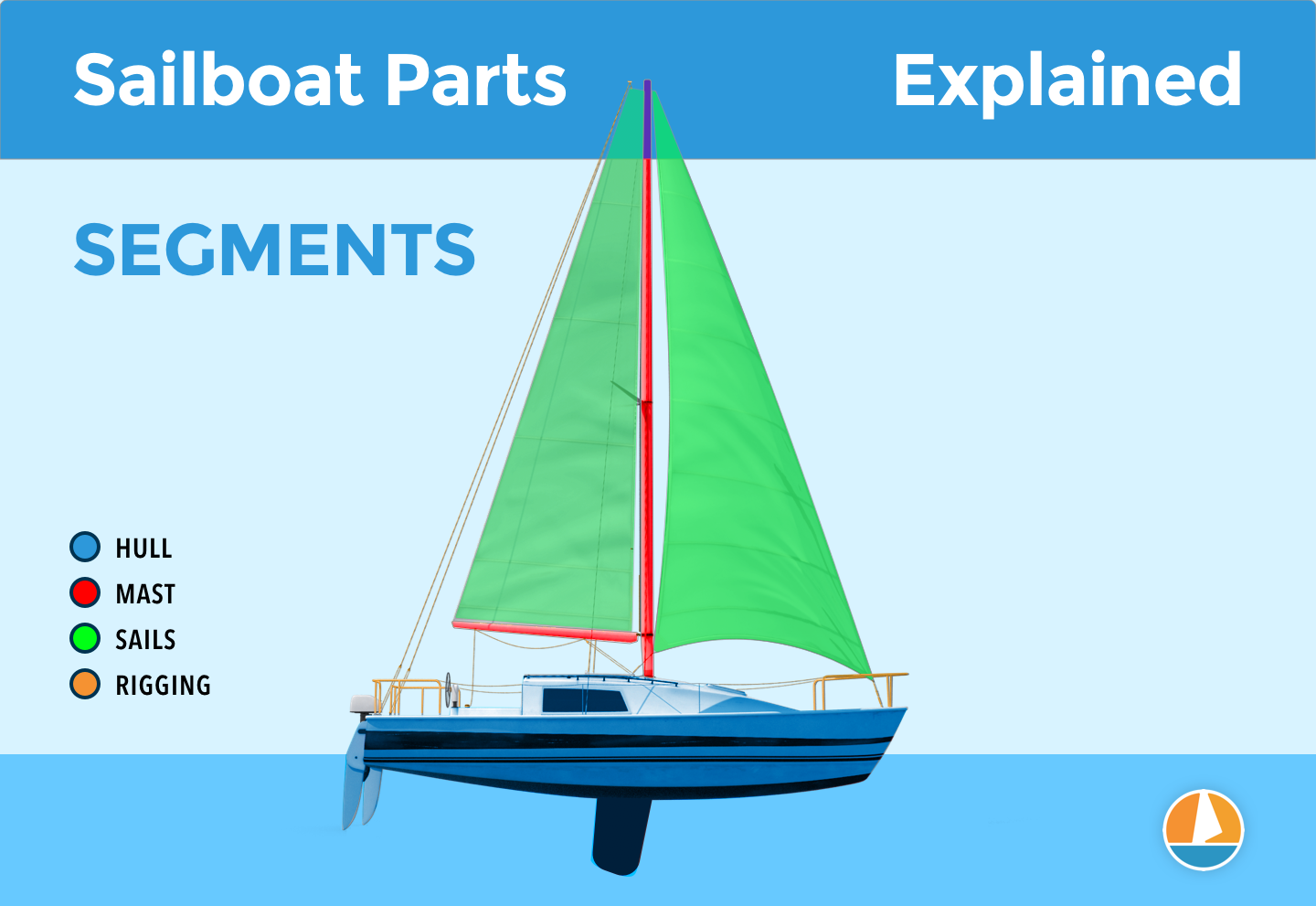

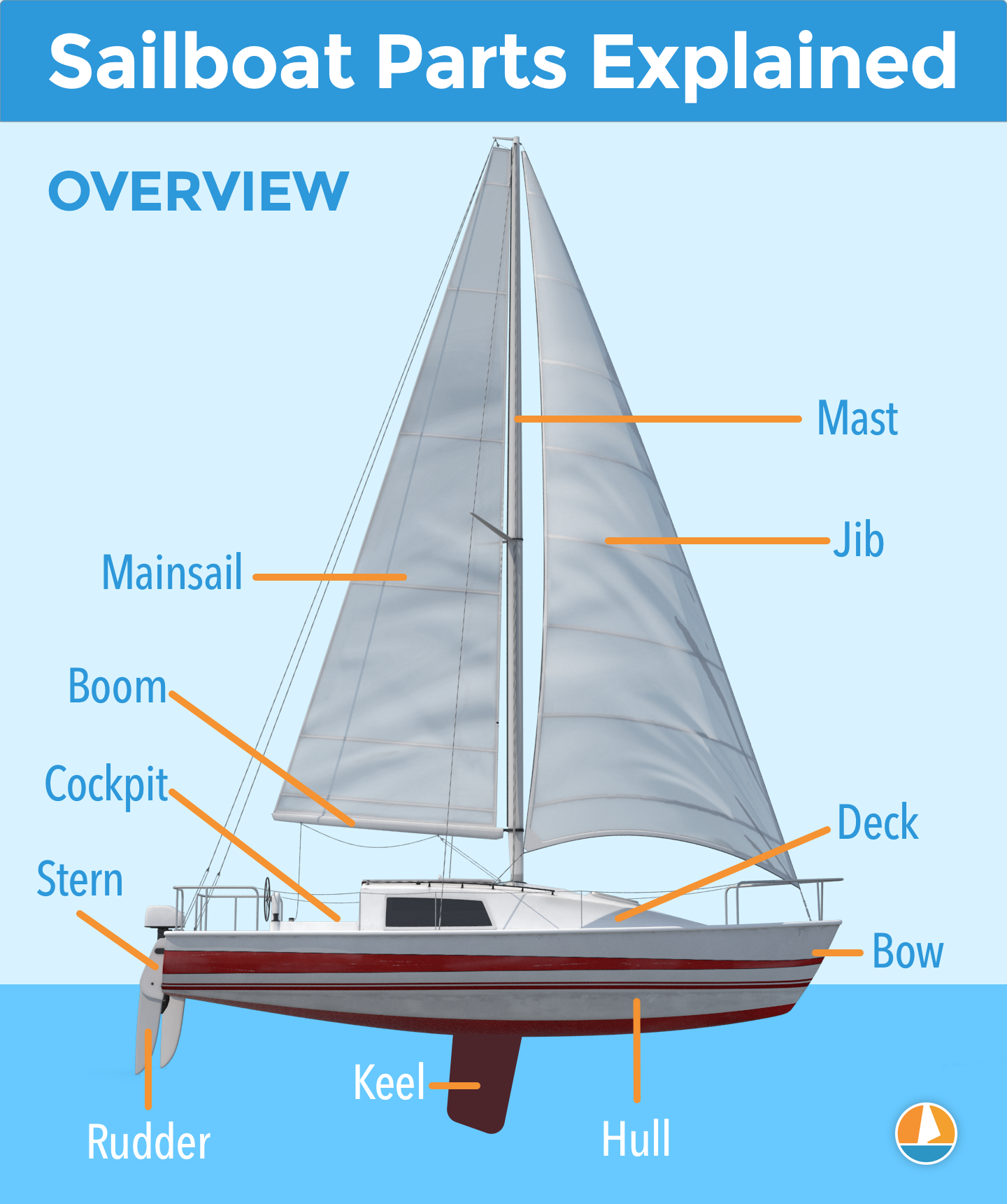

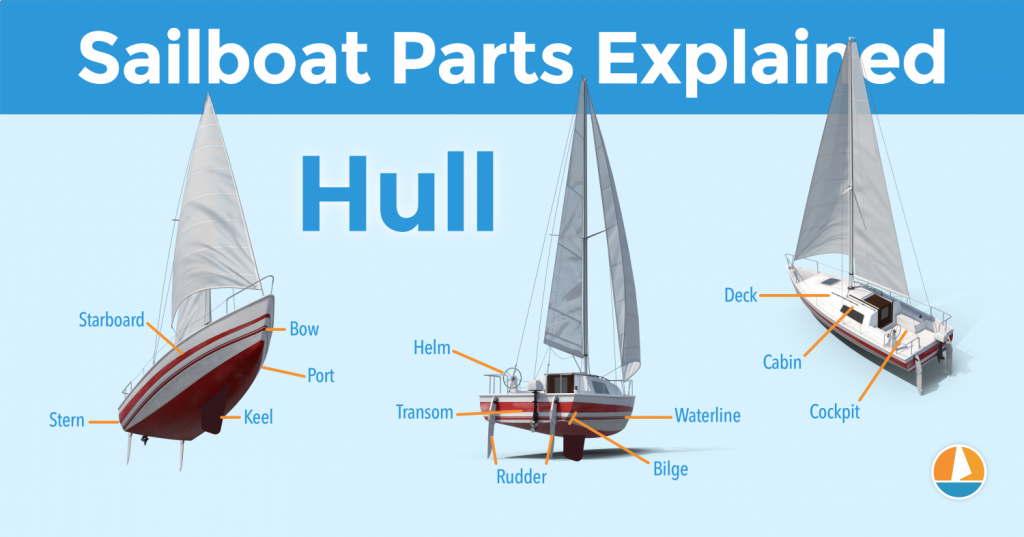

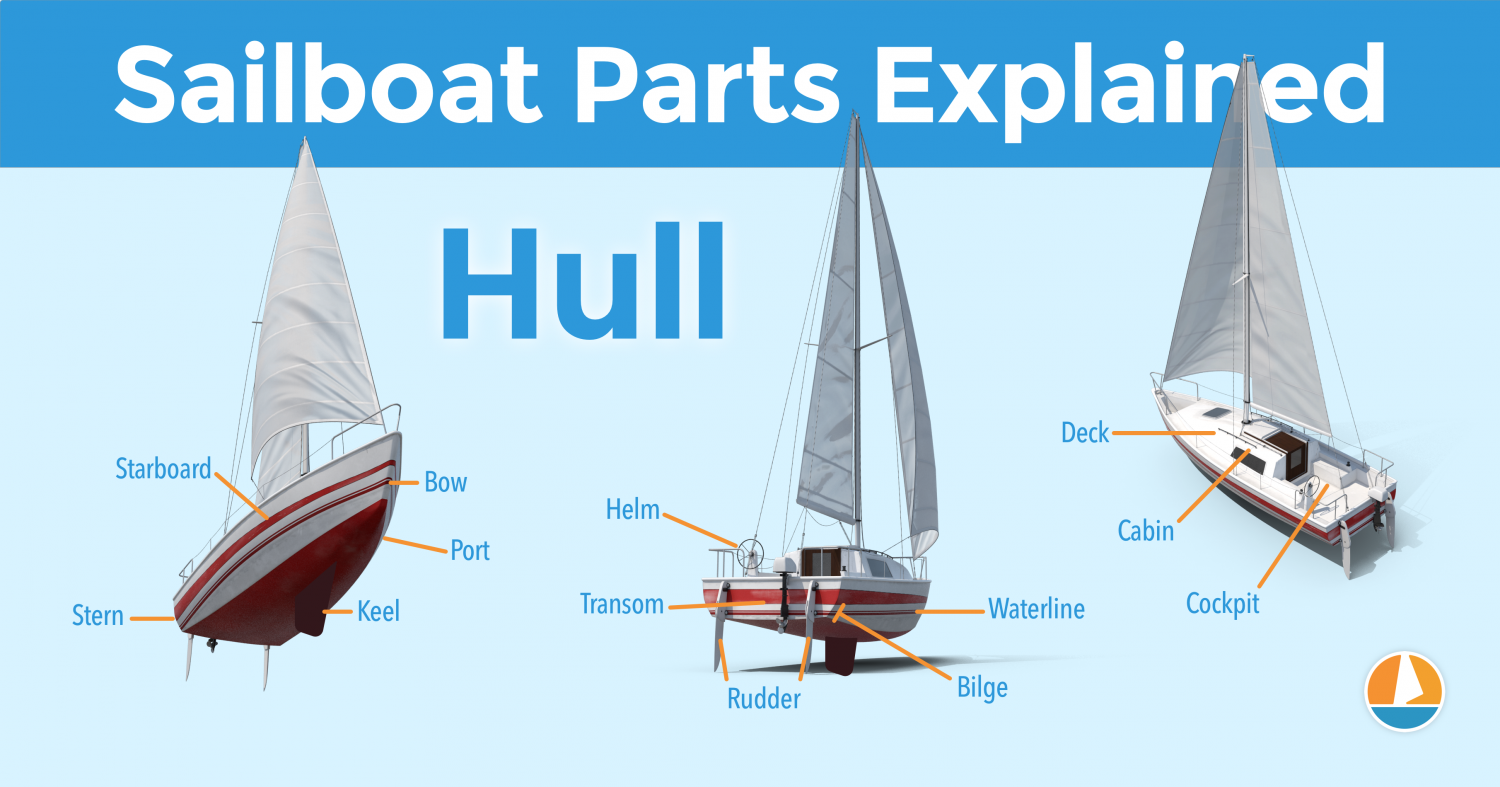

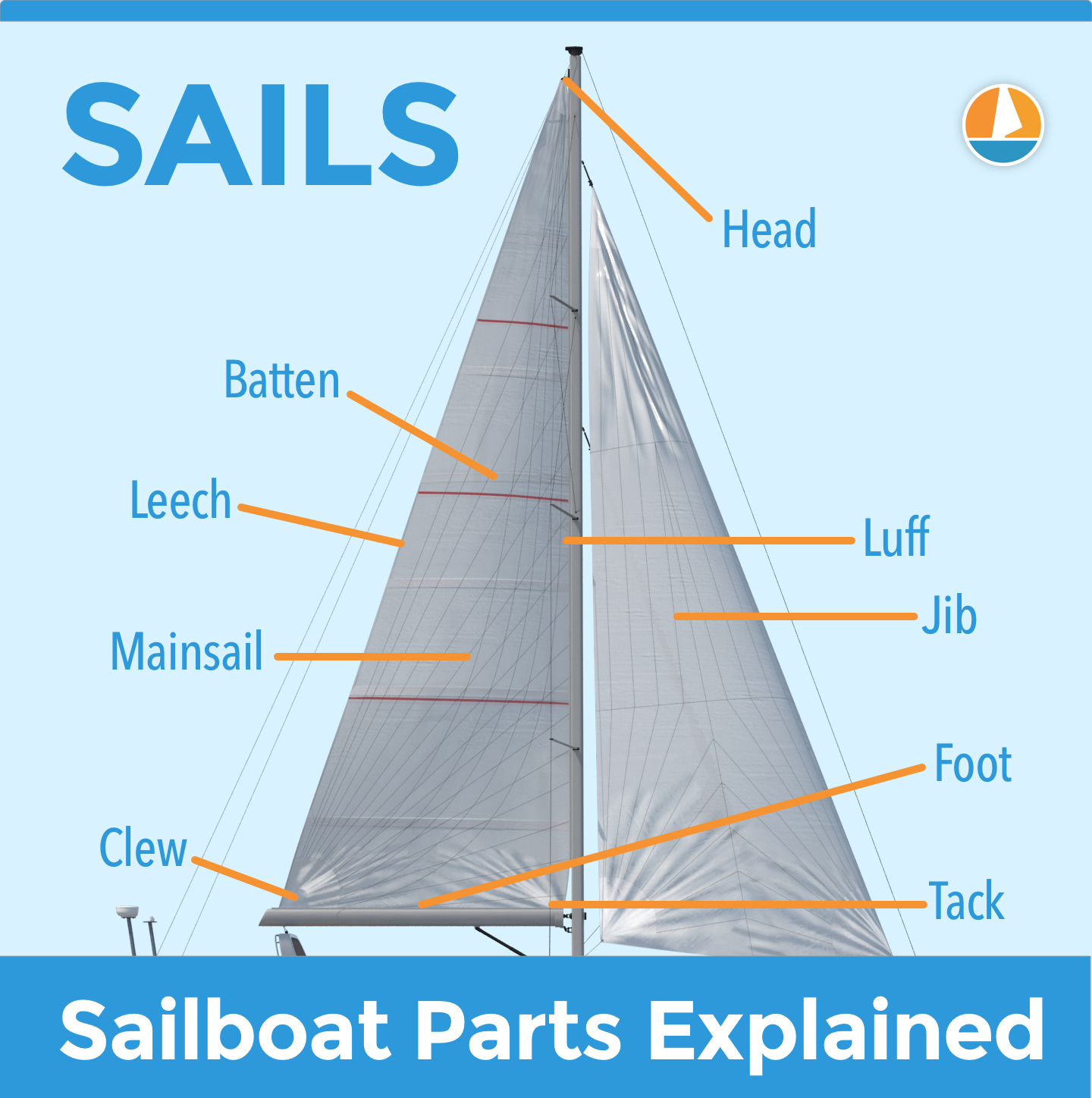

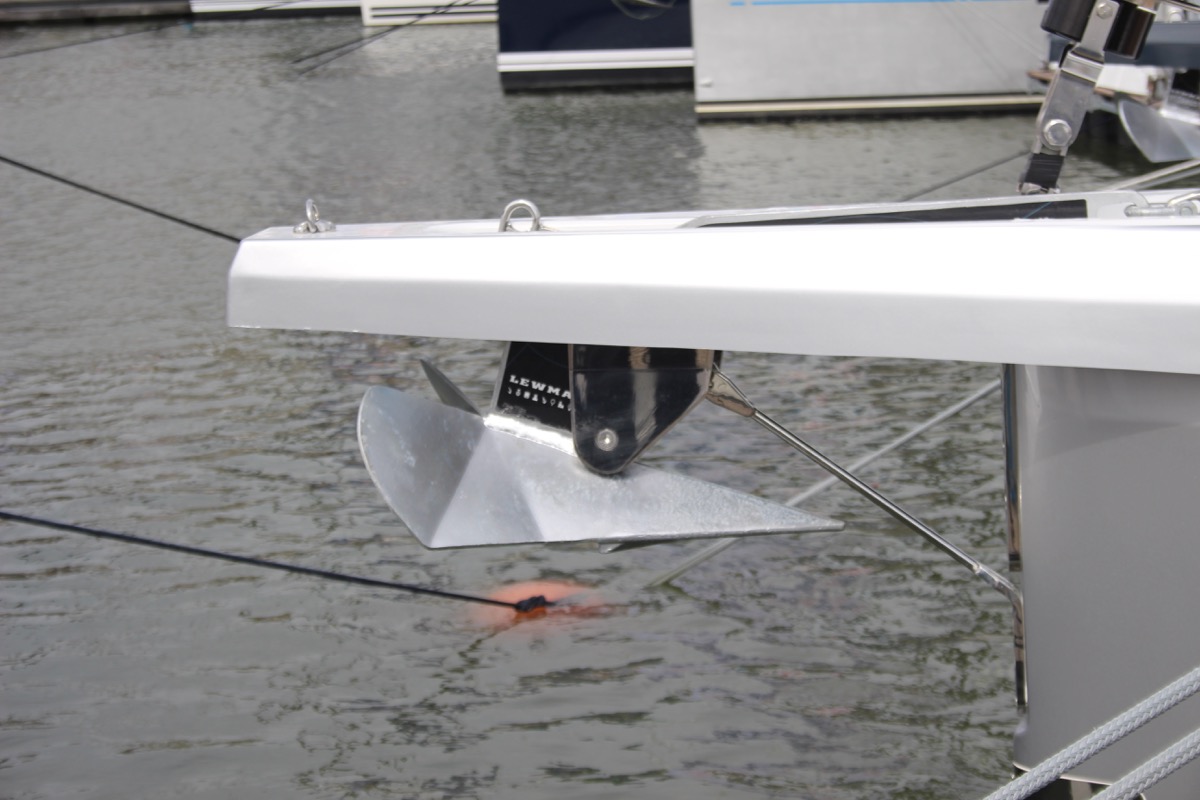

- Parts of a Sailboat

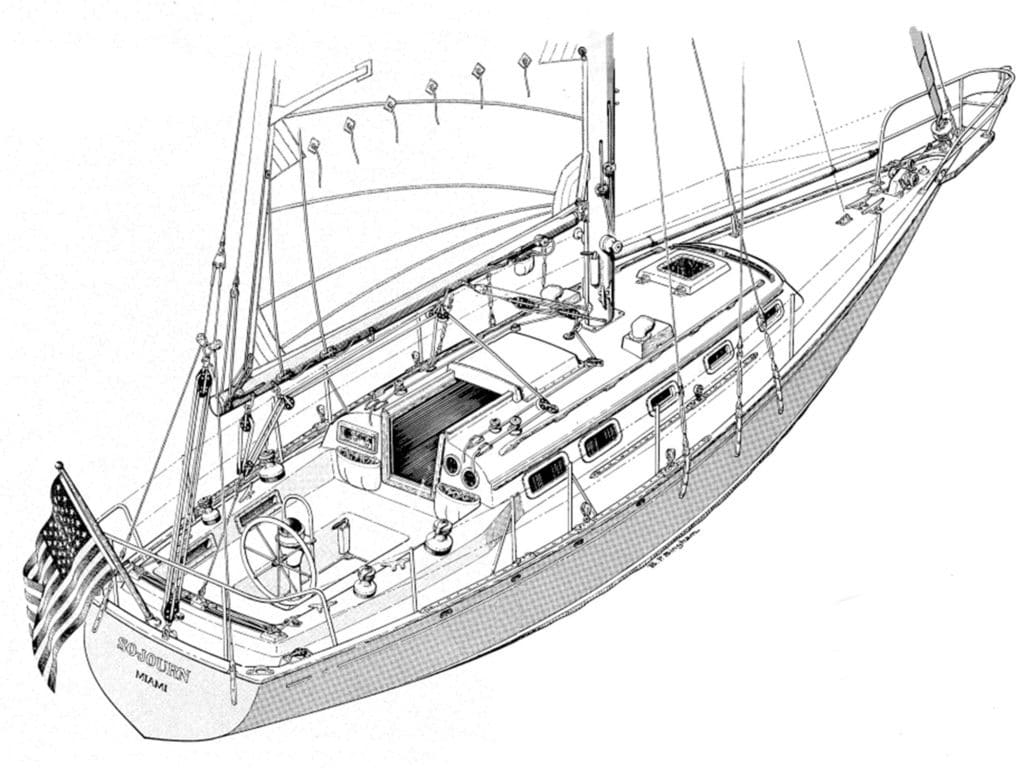

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

- Running Rigging

Sailboat Rigging: Part 2 - Running Rigging

Sailboat rigging can be described as being either running rigging which is adjustable and controls the sails - or standing rigging, which fixed and is there to support the mast. And there's a huge amount of it on the average cruising boat...

- Port and starboard sheets for the jib, plus two more for the staysail (in the case of a cutter rig) plus a halyard for each - that's 6 separate lines;

- In the case of a cutter you'll need port and starboard runners - that's 2 more;

- A jib furling line - 1 more;

- An up-haul, down-haul and a guy for the whisker pole - 3 more;

- A tackline, sheet and halyard for the cruising chute if you have one - another 3;

- A mainsheet, halyard, kicker, clew outhaul, topping lift and probably three reefing pennants for the mainsail (unless you have an in-mast or in-boom furling system) - 8 more.

Total? 23 separate lines for a cutter-rigged boat, 18 for a sloop. Either way, that's a lot of string for setting and trimming the sails.

Many skippers prefer to have all running rigging brought back to the cockpit - clearly a safer option than having to operate halyards and reefing lines at the mast. The downside is that the turning blocks at the mast cause friction and associated wear and tear on the lines.

The Essential Properties of Lines for Running Rigging

It's often under high load, so it needs to have a high tensile strength and minimal stretch.

It will run around blocks, be secured in jammers and self-tailing winches and be wrapped around cleats, so good chafe resistance is essential.

Finally it needs to be kind to the hands so a soft pliable line will be much more pleasant to use than a hard rough one.

Not all running rigging is highly stressed of course; lines for headsail roller reefing and mainsail furling systems are comparatively lightly loaded, as are mainsail jiffy reefing pennants, single-line reefing systems and lazy jacks .

But a fully cranked-up sail puts its halyard under enormous load. Any stretch in the halyard would allow the sail to sag and loose its shape.

It used to be that wire halyards with spliced-on rope tails to ease handling were the only way of providing the necessary stress/strain properties for halyards.

Thankfully those days are astern of us - running rigging has moved on a great deal in recent years, as have the winches, jammers and other hardware associated with it.

Modern Materials

Ropes made from modern hi-tech fibres such as Spectra or Dyneema are as strong as wire, lighter than polyester ropes and are virtually stretch free. It's only the core that is made from the hi-tech material; the outer covering is abrasion and UV resistant braided polyester.

But there are a few issues with them:~

- They don't like being bent through a tight radius. A bowline or any other knot will reduce their strength significantly;

- For the same reason, sheaves must have a diameter of at least eight times the diameter of the line;

- Splicing securely to shackles or other rigging hardware is difficult to achieve, as it's slippery stuff. Best to get these done by a professional rigger...

- As you may have guessed, it's expensive stuff!

My approach on Alacazam is to use Dyneema cored line for all applications that are under load for long periods of time - the jib halyard, staysail halyard, main halyard, spinnaker halyard, kicking strap and checkstays - and pre-stretched polyester braid-on-braid line for all other running rigging applications.

Approximate Line Diameters for Running Rigging

But note the word 'approximate'. More precise diameters can only be determined when additional data regarding line material, sail areas, boat type and safety factors are taken into consideration.

Length of boat

Spinnaker guys

Boom Vang and preventers

Spinnaker sheet

Genoa sheet

Main halyard

Genoa / Jib halyard

Spinnaker halyard

Pole uphaul

Pole downhaul

Reefing pennants

Lengthwise it will of course depend on the layout of the boat, the height of the mast and whether it's a fractional or masthead rig - and if you want to bring everything back to the cockpit...

Read more about Reefing and Sail Handling...

Headsail Roller Reefing Systems Can Jam If Not Set Up Correctly

When headsail roller reefing systems jam there's usually just one reason for it. This is what it is, and here's how to prevent it from happening...

Single Line Reefing; the Simplest Way to Pull a Slab in the Mainsail

Before going to the expense of installing an in-mast or in-boom mainsail roller reefing systems, you should take a look at the simple, dependable and inexpensive single line reefing system

Is Jiffy Reefing the simplest way to reef your boat's mainsail?

Nothing beats the jiffy reefing system for simplicity and reliability. It may have lost some of its popularity due to expensive in mast and in boom reefing systems, but it still works!

Recent Articles

The CSY 44 Mid-Cockpit Sailboat

Sep 15, 24 08:18 AM

Hallberg-Rassy 41 Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Sep 14, 24 03:41 AM

Amel Kirk 36 Sailboat Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Sep 07, 24 03:38 PM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

- Anchoring & Mooring

- Boat Anatomy

- Boat Culture

- Boat Equipment

- Boat Safety

- Sailing Techniques

Sailboat Running Rigging Explained

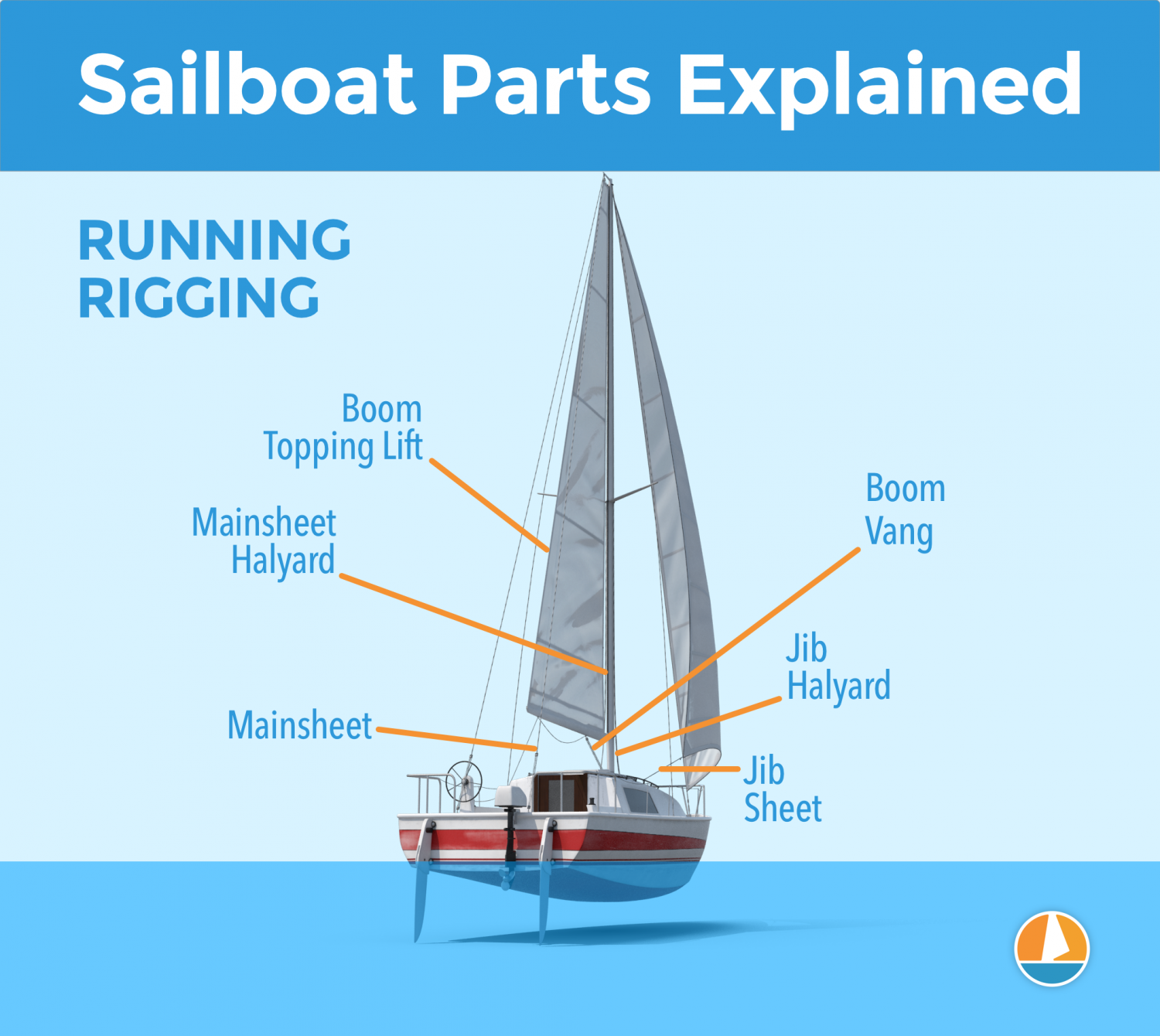

Running rigging refers to the essential lines, ropes, and hardware responsible for controlling, adjusting, and managing the sails on a sailboat. They directly impact a sailboat’s performance, maneuverability, and overall safety.

As a result, understanding different running rigging components and their functions can help us optimize our boat’s performance and make informed decisions in various sailing situations. This comprehensive guide delves deep into the world of rigging by examining its essential components and various aspects, including materials, maintenance, advancements, troubleshooting, knots, and splices.

Key Takeaways

- Running rigging consists of movable components like halyards, sheets, and control lines that control, adjust, and handle the sails.

- Synthetic materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran have revolutionized running rigging due to their superior strength-to-weight ratio, low stretch and abrasion resistance, and increased lifespan.

- Troubleshooting common running rigging problems involves untangling or untwisting lines, resolving jammed or stuck hardware, and ensuring lines hold tension correctly.

- Knowing how to tie knots and splice lines is crucial in connecting running rigging components, securing lines, and adjusting sails.

- To achieve the best performance, the boat's rigging should be tailored to specific sailing needs, either racing or cruising.

- Different sailboat types and configurations require specific running rigging setups.

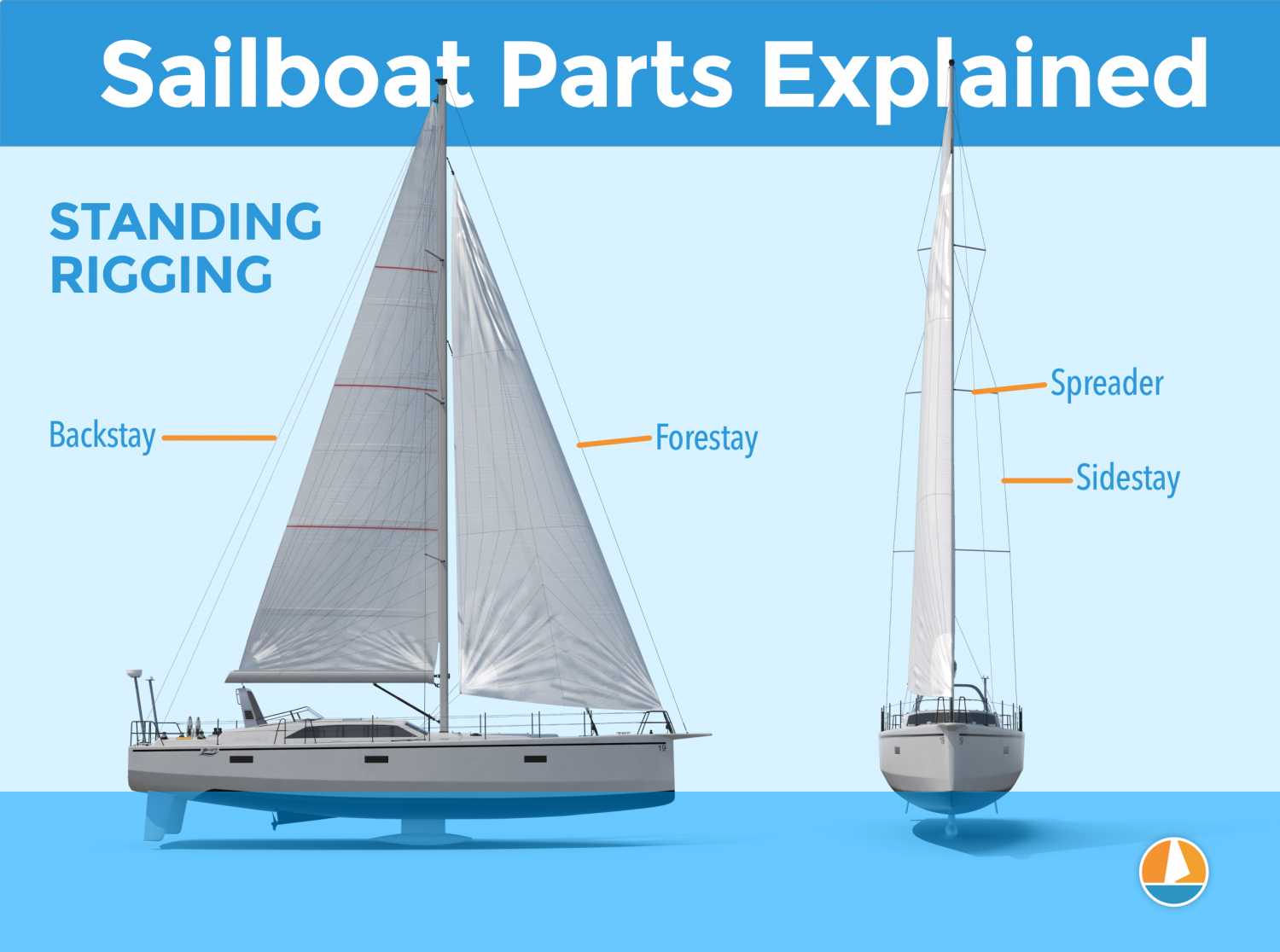

Difference between running and standing rigging

Before diving into the components, it’s essential to understand the difference between standing and running rigging. Standing rigging consists of the fixed lines, cables, and rods responsible for supporting a sailboat’s mast(s) and maintaining stability. Examples of standing rigging include shrouds, stays, and spreaders.

Running rigging, on the other hand, comprises the movable components needed to control, adjust, and handle the sails. These elements allow us to raise, lower, and trim the sails according to wind conditions and the boat’s course. Understanding the distinction between the two types of rigging is vital in operating a sailboat safely and efficiently.

Components of Running Rigging on a Sailboat

Responsible for raising, lowering, and holding sails in their deployed position. The primary types include the main halyard (for the mainsail), jib halyard (for jibs or genoas), and spinnaker halyard (for spinnakers). They typically run from the head of the sail down to mast-mounted winches or lead back to the cockpit for easy adjustment.

Control the angle of a sail relative to the wind. They connect the clew to the deck or another part of the rigging (e.g., tack), allowing adjustments and fine-tuning of sail trim . The two main types of sheets are mainsheets (for mainsails) and jib/genoa sheets (for headsails).

Control Lines

Essential for adjusting the tension and shape of sails. Examples include outhauls (for foot tension), cunninghams (for luff tension), and reef lines (for reducing the area under high wind conditions). Proper use of these lines allows sailors to optimize sail shape, improve efficiency, and manage their boats in various wind conditions.

Maintenance and Care

Regular inspection.

Routine inspection of your rigging is essential to identify wear, damage, or issues before they escalate into severe problems. Conduct a thorough examination at least once a season or more frequently if you sail extensively. When inspecting, check for signs of chafe, abrasion, corrosion, frayed, or damaged rope sections. Address these issues promptly to prevent further complications.

Cleaning and maintaining

Proper cleaning and maintenance of your rigging will improve its lifespan and maintain its performance. Rinse ropes and cordage with fresh water and mild detergent, if necessary. Lubricate and clean hardware components using marine-grade products, following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

When to replace

Advantages and impact of advanced synthetic materials , advantages of synthetic materials.

- Higher strength-to-weight ratio: Advanced materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran provide impressive strength while remaining lightweight, ensuring a secure connection and control in an easy-to-handle braid

- Low-stretch and abrasion resistance: These materials are incredibly resistant to stretching, providing improved control and accurate responsiveness. They also maintain their integrity and durability in wear, abrasion, and weathering.

- Increased lifespan: Synthetic materials can endure harsh conditions and resist UV damage.

Impact on Sailing Experience

The use of advanced materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran has had a profound effect on the sailing experience, with benefits including:

- Improved sail control and responsiveness: These low-stretch materials allow precise, user-friendly, and efficient sail handling and adjustments, leading to better overall performance.

- Enhanced durability and reduced maintenance: High-performance materials resist wear and weathering more effectively, increasing the lifespan of rigging and lowering the frequency of maintenance or replacement.

- Greater performance potential: Advanced materials’ increased strength and lightness improve boat performance to higher levels, especially in competitive racing scenarios.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

- Tangled or twisted lines: angled lines can impede adjustments and create hazardous situations, like tangled jib sheets , which can cause control issues with your headsail. Always coil and store lines properly when not in use to solve this issue. Regularly inspect your lines for twists or tangles, and address them before they become problematic.

- Jammed or stuck hardware: Dirt, corrosion, or damage can cause hardware components like blocks or winches to jam or stick, making it difficult to control the lines. Clean and lubricate your hardware according to the manufacturer’s guidelines to fix this issue. Replace any damaged or worn-out components to ensure smooth operation.

- Lines slipping or not holding tension: Runners may sometimes slip from cleats or winches, causing the sail to lose its desired shape or position. To overcome this issue, ensure you use the proper cleating or winching techniques, and double-check the compatibility of your line materials with your hardware.

When to call a professional

Although boat owners can resolve many rigging issues, there are situations where the expertise of a professional rigger may become necessary. Consider consulting a professional when:

- You feel uncertain about your ability to diagnose or fix a problem safely and effectively

- You need to replace or install new running rigging components that require specialized knowledge or skills

- You have encountered complex issues that may require advanced troubleshooting techniques

The Art of Knots and Splices

Importance of knots and splices.

Knots and splices connect rigging components, secure lines, and adjust sails. Proper knowledge and execution of these techniques allow us to:

- Effectively connect lines and hardware

- Quickly and safely secure or adjust lines under various conditions

- Reduce the risk of lines slipping or coming undone while sailing

- Maintain the integrity and strength of our rigging

Commonly used knots and their uses

Numerous knots are available for various purposes within the rigging. Some of the most common and versatile knots include:

- Bowline: This popular and secure knot is used for creating a fixed loop at the end of a line, often employed for attaching sheets to sails or halyards to shackles.

- Cleat hitch: A handy knot that quickly and securely fasten lines to cleats; widely used for halyards, sheets, and dock lines.

- Figure eight: A practical stopper knot prevents lines from slipping through hardware, such as blocks or clutches.

Techniques for splicing lines

Splicing is joining two lines or creating a loop within a single line by weaving rope fibers together. Splicing often results in stronger, more secure connections than tying knots and can improve the overall aesthetic of your rigging. Some techniques include:

- Eye splice: This technique creates a fixed loop at the end of a line, ideal for attaching hardware, such as thimbles, shackles, or blocks.

- Short splice: This method joins two lines by interweaving their ends, resulting in a strong connection suitable for halyards or sheets.

- End-to-end splice: An effective way to join two lines end-to-end, maintaining the line’s integrity and minimizing chafe or bulk.

Safety Practices When Handling Running Rigging

Basic safety rules.

- Be aware of your surroundings: Before making any adjustments to your sails or lines, evaluate the environment, and pay attention to potential hazards, such as nearby boats, obstacles, or changing wind conditions.

- Communicate clearly: When making adjustments or performing maneuvers, communicate your intentions with your crew to prevent confusion and ensure necessary steps are started promptly and coordinated.

- Use appropriate gear: Wear gloves to protect your hands from rope burns, and always have a knife or multi-tool nearby to handle unexpected situations, such as cutting tangled or jammed lines.

Risk and injury prevention

While handling rigging, take precautions to prevent accidents or injuries:

- Maintain proper body positioning: When working with lines or winches, position yourself securely to avoid sudden slips or loss of balance that could result in injuries.

- Keep fingers clear: Be cautious when handling lines around winches or cleats to prevent pinched fingers or rope burns.

- Avoid standing in a “line of fire”: Be mindful of potential line snap-backs or sudden movements when tension is released from sails or hardware.

Emergency procedures related to rigging

Being prepared for emergencies is crucial. Familiarize yourself with procedures such as:

- Man Overboard Recovery: Practice techniques to quickly stop the boat and retrieve someone who has fallen overboard.

- Rapid sail reduction or deployment: In extreme weather or urgent situations, know how to quickly reef, furl, or set sails to maintain control and stability.

Tips and Techniques for Better Performance

Tips for optimizing performance.

- Regular inspection and maintenance: Ensuring your lines, hardware, and sails are in good condition and correctly cared for is crucial for performance optimization on the water.

- Tailor your rigging: Customize your rigging according to your specific requirements, whether racing or cruising, as this can affect your boat’s overall performance.

Techniques for Smoother Sailing

- Match line materials and diameters to their purpose: Select the proper line material and diameter for each rigging component, such as the mainsheet, to ensure better sail control, reduced friction, and smooth operation.

- Stay organized and avoid line clutter: Keep lines and hardware tidy using organizers and storage solutions to prevent tangles and confusion, leading to inefficiency or unsafe situations on the water.

Additional Sailboat Rigging Components and Techniques

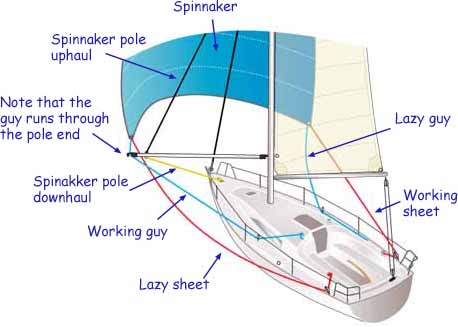

- Guys: These lines, in conjunction with spinnaker sheets, offer lateral control of the spinnaker pole and consequently allow better management of the spinnaker shape as they help balance the tension between forestay and backstay , maximizing its efficiency in downwind sailing.

- Vangs (or boom vang or kicking strap): While controlling the boom’s angle to maintain shape, vangs also help prevent accidental gybes, increasing safety on board.

- Outhauls: By managing foot tension and the sail hoist, outhauls aid in achieving optimal sail shape according to the wind conditions and point of sail . Loosening the outhaul creates a deeper shape for light winds, while tightening it flattens the sail for heavier conditions.

Equipment Organization and Storage

- Line bags or organizers: Store coiled lines for different sails, like staysail, and keep aft rolling furling lines neatly organized to minimize tangles and clutter.

- Clutches or labeled cleats: Label the appropriate hardware for each line to prevent confusion when adjusting sails.

- Winch handle holders: Ensure winch handles are secured in a designated holder when not in use, reducing the risk of accidents or loss overboard.

Different Rigging Setups

- Sloop Rig vs. Cutter Rig: A sloop rig typically has one headsail, like a genoa, while a cutter rig features two or more, requiring additional rigging components like adding extra backstays for support, extra halyards, sheets, and control lines for the cutter rig.

- In-Mast vs. In-Boom Furling Systems: These systems allow easy reefing and sail deployment. Running rigging for furling systems will include additional lines and hardware to manage furling and unfurling processes from the cockpit.

- Racing Boats vs. Cruising: Racing boats may require specialized configurations, such as high-performance lines and lightweight hardware, while cruising sailboats may prioritize more versatile, durable, and easy-to-maintain rigging components.

Final Thoughts

Understanding and effectively managing running rigging is critical to sailing, directly affecting the boat’s performance, maneuverability, and safety. This comprehensive guide offers a detailed breakdown of rigging components, their care and maintenance, troubleshooting, and the essential knots and splices. It also explores the revolutionary impact of synthetic materials, provides safety practices, and highlights the importance of customizing your running rigging according to your sailing needs.

Standing rigging refers to the fixed lines, cables, and rods that support the sailboat’s mast and maintain stability. Running rigging refers to the movable components that control, adjust, and handle the sails.

Critical components of running rigging include halyards, sheets, and control lines. Additional components can consist of guys, vangs, and outhauls.

Synthetic materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran offer superior strength-to-weight ratio, low stretch and abrasion resistance, and an increased lifespan, resulting in better control and durability of running rigging components.

Ideally, if you sail extensively, you should inspect your running rigging at least once a season or more frequently if you sail extensively. Regular cleaning, lubrication, and replacement of worn-out components should be part of your maintenance routine.

Different sailboat types and sail configurations may require specific running rigging setups. For example, a sloop rig and cutter rig have additional requirements for headsails, thus requiring various running rigging components. Similarly, racing boats and cruising sailboats may require different running rigging setups to cater to their needs.

The Importance of the Sailboat Comfort Ratio

What is an impeller on a boat, related posts, whisker pole sailing rig: techniques and tips, reefing a sail: a comprehensive guide, sail trim: speed, stability, and performance.

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Statement

© 2023 TIGERLILY GROUP LTD, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London, WC1N 3AX, UK. Registered Company in England & Wales. Company No. 14743614

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Add New Playlist

- Select Visibility - Public Private

Running Rigging

Jib Tack, Jib Halyabds, and Jib Sheets.

The jib tack requires to be of great strength, and is made indifferently, accordingly to the judgment of the person who has the fitting out of the yacht, of rope, chain, or flexible wire rope. Rope does very well in vessels under 40 tons, but wire is to be preferred, and it is found to stand better than chain. The jib tack t is fast to the traveller a (Fig. 15), and leads down through a sheave hole * at the bowsprit end (inside the cranse iron) a block is shackled to the end of the tack through which the outhaul is rove. The standing part of the outhaul is put over one of the bitts with a running eye; the hauling part leads on board by the side of the bowsprit. A single rope inhaul is generally fast to the traveller.

The score in the end of the bowsprit has necessarily to be very large, and frequently it is made wider than it need be; at any rate the sheave hole is a source of weakness, and generally if the end of the bowsprit comes off it is close outside the sheave hole, the enormous lateral strain brought on the part by the weather shroud (%) causing the wood to give way. To avoid such accidents as these one or two yachts have the sheave outside the iron, as shown by to. The tack n passes between the ears or "lugs" on the cranse iron at o and p. To o the topmast stay is fitted, and the bobstay block at p. Of course if the score and sheave were put at m, the other score and sheave * would be dispensed with. Generally when the end comes off at the sheave 8 the bowsprit immediately afterwards breaks close off at the stem, unless some one is very smart at letting the jib sheets fly, or in putting the helm down. With the sheave hole at m no such accident would happen.

Jib halyards are, as a rule, made of chain, as it runs better and does not stretch, and the fall stows in a smaller compass when the jib is set; in fact, the fall is generally run through one of the chain pipes

into the forecastle, where it helps a trifle as ballast.* However, several large vessels, such as Livonia, Modwena, and Arrow, have had Manilla rope. The jib halyards are rove through an iron (single) block (which is hooked or shackled to the head cringle of the jib), and then each part leads through an iron (single) block on either side of the masthead (see Fig. 5). The hauling part usually leads down the port side of the mast; the purchase is shackled to the part that leads through the block on the starboard side. In vessels above 40 tons a flexible wire runner is invariably used in addition to the purchase; one end of the runner is shackled to an eye bolt on deck, and the other, after leading through a block on the end of the jib halyard, is shackled to the npper block of the purchase. The purchase consists of a double and single block, or two double; in the former case the single block is below, with the standing part of the tackle fast to it; but where two blocks are used, the standing part of the tackle is made fast to the upper block. As a great deal of "beef" is required to properly set up a jib, it is usual to have a lead of some kind for the " fall" * of the purchase on deck, such as a snatch block. It is, of course, necessary to have a " straight" luff to a jib, but very frequently the purchase is used a little too freely; the result is that the forestay is slacked, and perhaps a link gives way in the halyards; or the luff rope of the jib is stranded (generally near the head or tack, where it has been opened for the splice), and sometimes the bobstay-fall is burst. (We once saw the latter mishap occur on board the Oimara during the match at Southsea.) These mishaps can be generally averted by "easing" the vessel whilst the jib is being set up, choosing the time whilst she is in stays or before the wind, and watching to see that the forestay is not slackened.

Jib sheets in vessels under 80 tons are usually single, but in vessels larger than 80 tons they are double. In the latter case there are two blocks, which are put on the clew cringle; a sheet is rove through each block, and the two parts through the jib sheet holes in the wash strake of the bulwarks; one part of the sheet is then made fast and the other hauled upon.

Fobs Halyards, Fobe Tacks, and Fobb Shebts.

The fore halyards are usually fitted as follows: The standing part is hooked or shackled to an eye bolt under the yoke on the port side, then through a single block hooked to the head of the sail, and up through another single block hung to an eye bolt under the yoke on the starboard side. The downhaul is bent to the head cringle or to the hook of the

* The "fell" of a tackle is the pert that is taken hold of to haul upon.

block. No purchase is necessary, as the sail is set on a stay; but in yachts above 10 tons the luff of the sail is brought taut by a tackle hooked to the tack; the tack leads through the stem head. The tackle oonsists of a single and double block, or two doubles according to the size of the yacht. In yachts of 40 tons and upwards the tack is usually made of flexible wire rope.

Fore sheets in yachts under 15 tons are usually made up of two single blocks. The standing part is made fast to the upper block (hooked and moused or shackled to the clew of the sail). In larger vessels a double, or single, or two double blocks are used, the hauling part or fall always leading from the upper block. In very large vessels, such as 100-ton cutters or yawls, or 140-ton schooners , "runners" are used in addition to tackles. These are called the standing parts of the sheets: one end is hooked on the tackle by an eye; the other end is passed through a bullseye of lignum vitss on the clew of the sail, and is then belayed to a cavel. The sail is then Bheeted home with the tackle.

Main and Peak Halyards, Main Tack, Main Sheet, and Main

The main or throat halyards are generally rove through a treble block at the masthead, and a double block on the jaws of the gaff. The hauling part of the main halyards leads down the starboard side of the mast, and is belayed to the mast bitts. The main purchase is fast to the standing part, and usually consists of a oouple of double blocks, and the lower one is generally hooked to an eye bolt in the deck on the starboard side. In vessels under 15 tons it is unusual to have a main purchase, and when there is no purchase the upper main halyard block is a double one, and the lower a single. However, racing 10-tonners have a main purchase, and many 5-tonners have one. The principal object in having a main purchase in a small craft is that the mainsail can be set better, as in starting with "all canvas down" the last two or three pulls become very heavy, especially if the hands on the peak have been a little too quick; and a much tauter luff can be got by the purchasfl^than by the main tack tackle. Of course the latter is dispensed with in small vessels where the purchase is used, and the tack made fast by a lacing round the goose-neck of the boom. By doing away with the tack tackle at least 6in. greater length of luff can be had in a 5-tonner, and this may be of some advantage. The sail cannot be triced up, of course, without casting off the main tack lacing; but some yacht sailers oonsider this an advantage, as no doubt sailing a vessel in a strong wind with the main tack triced up very badly stretches the sail, looks very ugly.

The peak halyards in almost all vessels under 140 tons are rove through two single blocks on the gaff and three on the masthead, as shown in Plate I. and Fig. 5. Some vessels above 140 tons have three blocks on the gaff, and in such cases the middle block on the masthead is usually a double one. The standing part of the peak halyards to which the purchase is fast leads through the upper block and down on the port side.

The usual practice in racing vessels is to have a wire leather-covered span (copper wire is best) with an iron-bound bullseye for each block on the gaff to work upon, and this plan no doubt causes a more equal distribution of the strain on the gaff. The binding of the bullseye

has an eye to take the hook of the block. In Fig. 16 a is a portion of the gaff, b is the span; c c are the eyes of the span and thumb cleats on the gaff to prevent the eyes slipping, d is the bullseye with one of the peak halyard blocks hooked to it.

The main tack generally is a gun tackle purchase, but in vessels above 60 tons a double and single or two double blocks are used. In addition, some large cutters have a runner rove through the tack cringle, one end being fast to the goose-neck of the boom, and the other to the tackle. In laced mainsails the tack is secured by a lacing to the goose-neck.

The main boom is usually fitted to the spider hoop round the mast by a universal joint usually termed the main boom goose-neck.

The main sheet should be made of left-handed, slack-laid, six-stranded Manilla rope. The blocks required are a three-fold on the boom, a two-fold on the buffer or hone, as the case may be, and a single block on each quarter for the lead. Yachts of less than 15 tons have a double block on the boom, and single on the buffer.

Many American yachts have a horse in length about one-third the width of the counter for the mainsheet block to travel on. For small vessels, at any rate, this plan is a good one, as the boom can be kept down so much better on a wind, as less sheet will be out than there would be without the horse. A stout ring of indiarubber should be on either end of the horse, to relieve the shock as the boom goes over.

The mainsail outhaul is made np of a horse on the boom, a shackle as traveller, a wire or chain runner outhaul (attached to the shackle, and rove through a sheave hole at the boom end), and a tackle. (See Fig. 17.) In small vessels the latter consists of one block only; in large vessels of two single, or a double and single, or two double blocks.

The old-fashioned plan of outhaul, and one still very much in use, consists of an iron traveller (a large leather-covered ring) on the boom end, a chain or rope through a sheave hole and a tackle. This latter plan is perhaps the stronger of the two; but an objection to it is that the traveller very frequently gets jammed and the reef cleats have to be farther forward than desirable, to allow the traveller to work.

Sometimes, instead of a sheave hole, the sheave for the outhaul is fitted right at the extreme end of the boom, on to which an iron cap is fitted for the purpose.

Topsail Halyards, Sheets, and Tacks.

The topsail halyards in vessels under 10 tons consist of a single rope rove through a sheave hole under the eyes of the topmast rigging.

Yachts of 10 tons and over have a block which hooks to a strop or sling on the yard, or if the topsail be a jib-headed one, to the head cringle. The standing part of the halyard has a running eye, which is put over the topmast, and rests on the eyes of the rigging; the halyard is rove through the block (which has to be hooked to the yard), and through the sheave hole at the topmast head. It is best to have a couple of thumb cleats on the yard where it has to be slung; there is then no danger of the strop slipping, or of the yard being wrongly slung.

When the topsail yard is of great length, as in most yachts of 40 tons and upwards, an upper halyard is provided (called also sometimes a tripping line or trip halyard, becausfe the rope is of use in tripping the yard in hoisting or lowering). This is simply a single rope bent to the upper part of the yard, and rove through a sheave hole in the pole, above the eyes of the topmast rigging. The upper halyards are mainly useful in hoisting and for lowering to get the yard peaked; however, for very long yards, if bent sufficiently near the upper end, they may in a small degree help to keep the peak of the sail from* sagging to leeward, or prevent the yard bending.

The topsail sheet is always a single * Manilla rope, as tarred hemp rope would stain the mainsail in wet weather. It leads through a cheek block on the gaff end, then through a block shackled to an eye bolt under the jaws of the gaff; but in most racing vessels nowadays a pendant or whip is used for this block, as shown in Plate I. The pendant should go round the mast with a running eye. By this arrangement the strain is taken off the jaws of the gaff and consequently off the main halyards. A common plan of fitting this block and whip is shown in Pig. 18. The hauling part of the sheet is generally put round one of the winches on the mast to " sheet home " the topsail.

The topsail tack is usually a strong piece of Manilla with a thimble spliced in it, to which the tack tackle is hooked.

Jib-topsail halyards and main-topmast-staysail halyards are usually single ropes rove through a tail block on topmast head; but one or two large vessels have a lower block, with a spring hook, which is hooked to the head of the sail. In such cases, the standing part of the halyards is fitted on the topmast head with a running eye or bight.

• The Oimara, cutter, had doable topsail sheets rove in this way : one end of the sheet was made fast to the gaff end; the other end of the sheet was rove through a single block on the clew of the sail; then through the oheek block at the end of the gaff, through a block at the jaws of the gaff, and round the winch.

Spinnaerb Halyards, Outhaul, &c.

Spinnaker halyards are invariably single, and rove through a tail block at the topmast bead.

The spinnaker boom is usually fitted with a movable goose-neck at its inner end. The goose-neck consists of a universal joint and round-neck pin, and sockets. (Square iron was formerly used for the neck, but there was always a difficulty in getting the neck shipped in the boom, and round iron was consequently introduced.) The pin is generally put into its socket on the mast, and then the boom end is brought to the neck.

At the outer end of the boom are a couple of good-sized thumb cleats, against which the running eye of the after and fore guy are put. The fore guy (when one is used) is a single rope; the after guy has a pendant or whip with a block at the end, through which a rope is rove. The standing part of this rope is made fast to a cavel-pin on the quarter, and so is the hauling part when belayed. The after guy thus forms a single whip-purchase (see Plate I.). The outhaul is rove through a tail block* at the outer end of the spinnaker boom, and sometimes a snatch block is provided for a lead at the inner end on th§ mast. The topping lift consists of two single, a double and single, or two double blocks, according to the size of the yacht.

The upper block of the topping lift is a rope strop tail block, with a running eye to go round the masthead. The lower block is iron bound, and hooks to an eye strop on the boom.

Formerly a bobstay was used ; but, if the boom is not allowed to lift, it will bend like a bow; in fact, the bobstay was found to be a fruitful cause of a boom breaking, if there was any wind at all, and so bobstays were discarded. The danger of a boom breaking through its buckling up can be greatly lessened by having one hand to attend to the topping lift; as the boom rears and bends haul on the lift, and the bend will practically be "lifted" out.

Small yachts seldom have a fore guy to spinnaker boom, but bend a rope to the tack of the sail (just as the outhaul is bent) leading to the bowsprit end; this rope serves as a fore guy, or brace, to haul the boom forward; and when the spinnaker requires to be shifted to the bowsprit, the boom outhaul is slackened up and the tack hauled out to bowsprit end. Thus double outhauls are bent to the spinnaker tack cringle, and one

• Formerly a hole vu out in the boom end, and a sheaye fitted for the outhaul to run through; this plan is now abandoned, as, unless the boom happens to oome with one partionlar side uppermost, an unfair lead may result rove through the sheave hole or block at the spinnaker boom end, and the other through a block at bowsprit end. But generally the large spinnaker (set as such) has too much hoist for the jib spinnaker, and a shift has to be made for the bowsprit spinnaker, which is hoisted by the jib topsail halyards if that sail be not already set; even in such case no fore guy is used in small vessels, but to ease the boom forward one hand slackens up the topping lift a little, and another the after guy, and, if there be any wind at all, the boom will readily go forward. In a five-tonner the after guy is a single rope without purchase, and the topping lift is also a single rope, rove through a block under the lower cap.

A schooner has a main and fore spinnaker fitted in the manner just described, and the usual bowsprit spinnaker as well, which is usually hoisted by the jib topsail halyards.

As spinnaker booms are now carried so very long, they will not go under the forestay; consequently, when the spinnaker has to be shifted, the boom must be unshipped. To shift the boom, the usual practice is to top it up, lift it away from the goose-neck, and then launch the inner end aft till the outer end will clear the forestay, or leech of foresail if that sail be set. If the boom is not over long, the inner end can be lowered down the fore hatch or over the side of the vessel until the other end will clear the forestay (see als<J page 79).

When spinnakers were first introduced no goose-neck was used, the heel of the boom being lashed against the mast. A practice then sometimes was to have a sheave hole at either end of the boom, with a rope three times the length of the boom rove through each sheave hole. One end of this rope served as the outhaul, the other for the lashing round the mast. To shift over, the boom was launched across to the other rail, and what had been the inboard end became the outboard end. Of course the guys had to be shifted from one end to the other. As spinnaker booms are now of such enormous length, it would be almost impossible, and highly dangerous, to work them in this way, although it might do for a five-tonner.

Spinnaker booms when first fitted with the goose-neck were no longer than the length from deck to hounds, so that they could be worked under the forestay without being unshipped. However, it would appear that the advantages of a longer boom are greater than the inconvenience of having to. unship it for shifting, and now, generally, a spinnaker boom when shifted and topped up and down the mast, reaches above the upper cap.

The following plan was worked during the summer of 1876 in the Lily, 10-tonner, but we have never met with it elsewhere. The arrangement was thus described: Take a yacht of say 65 tons, and suppose her 70ft. long and 15ft. beam, with a mast measuring 60ft. from deck to cap, from which if 9ft. is subtracted for masthead, and 4ft. more allowed for the angle made by the forestay, a spinnaker boom, to swing over clear, cannot exceed 43ft. (as the goose-neck is 3ft. from deck), which of course is much too little to balance the mainboom and sail. It is proposed to have a boom of 42ft., and another smaller one of 21ft. made a little heavier than the long one, and fitted with two irons 7ft. apart; the longer one to be made in the usual manner, with bolts in both ends, for the goose-neck; but the sheaves in the ends to be, one vertical, and the other horizontal. It will then make a very snug storm boom for the balloon jib when shipped singly, whilst the smaller one, by leading a tack rope (or outhaul) through the block on the outer iron will do very well for the staysail. See Fig. 19: in case No. 1, the boom is on end and ready for letting fall to starboard; and in Ho. 2 dipped and falling to port. A A (No. 1) represents the 42ft. boom, and B B the 21-footer; the dotted line b b the arc the boom would travel if not let run down; and the dotted line c c the actual line it travels when housed. C in the small diagram represents the outer iron or cap on the end of the small

boom (which can be made square or round; in the diagram it is made square, to prevent twisting), and a a bolt to which the standing part of the heel rope is made fast by clip hooks; the rope passes through the horizontal sheave at h, and back to the block on the cap at/. The fall can be belayed to a cleat on the small boom, or would greatly ease the strain on the gooseneck if made fast on the rail or to the rigging. When gybing it would only be necessary to top the boom by the lift, let go the heel rope, and let it run down; then swing over, lower away, and haul out the boom when squared. It would be better to hook on the Burton purchase to the cap at e, both as an extra support and to make sure of the boom whilst swinging. This plan would not only obviate the danger and trouble of dipping the boom, but give a 57ft. spar, besides giving greater strength, the boom being double where the most strain comes; and the extra weight is a positive advantage, as helping to balance the main boom. Of course this plan would allow of almost any length of spars, as a 40ft. lower boom would give a 74ft. spar, and still leave 8ft. between the irons; and in these days of excessive spars and canvas no doubt it would be attempted to balance a ringtail, but the lengths given seem a good comparative length for any class.

A more simple plan for " telescoping " a spinnaker boom is shown by

Fig. 20, a is the inner part of the boom; c is a brass cylinder with an

angular slot in it at 8. This cylinder is fixed tightly to the outer part of the boom by the screw bolts i i. The two parts of the boom meet inside the cylinder at the ticked line t. When the two parts "of the boom are to be used together, the ring m is put on the cylinder. The inboard part of the boom is then put into the cylinder, and the whole is firmly screwed up by the thumb-screw x. Both parts of the boom have their ends " socketed " so as to take a goose-neck, and thus either part can be used alone.

Was this article helpful?

Recommended Programs

Myboatplans 518 Boat Plans

Related Posts

- Standing Rigging - Boat Sailing Guide

- Plan Drawing Fregatt - Rigging

- How Are Catamaran Masts Fixed Down

- Rigging a singlehanded dinghy

- Rigging a twohanded dinghy

- Rig Construction - Ship Design

Readers' Questions

What is yacht running rigging?

Yacht running rigging is the ropes and cables used to control the movement of the sails and spars of a sailing yacht. It generally consists of halyards, sheets, guys, and sometimes vangs, used to raise, lower, and angle the sails.

Please verify you are a human

Access to this page has been denied because we believe you are using automation tools to browse the website.

This may happen as a result of the following:

- Javascript is disabled or blocked by an extension (ad blockers for example)

- Your browser does not support cookies

Please make sure that Javascript and cookies are enabled on your browser and that you are not blocking them from loading.

Reference ID: af93ec3d-763d-11ef-9d07-2a63fa623612

Powered by PerimeterX , Inc.

Whats the Difference between Standing Rigging and Running Rigging?

Running rigging refers to the movable lines and ropes used to control the position and shape of the sails on a sailboat. Standing rigging, on the other hand, refers to the fixed wires and cables that support the mast and keep it upright.

As the sun rises on another day, we find ourselves immersed in a world where the sails of sailboats dance upon the seas, their intricate rigging patterns a testament to the artistry and engineering of seafaring. From the towering masts of schooners to the sleek lines of modern racing yachts, sailboat rigging represents a crucial element in the composition of these majestic vessels, an amalgamation of form and function that is as beautiful as it is essential.

With its intricacies and complexities, sailboat rigging is a subject that has captivated the hearts and minds of sailors and enthusiasts alike, drawing them into a world of knots, splices, and shrouds that is at once ancient and modern, traditional and innovative. So join us as we explore the types of sailboat rigging that exist, and discover the joys and challenges of this fascinating and endlessly rewarding pursuit.

Standing Rigging

Standing rigging is the system of cables, rods, and wires that support the mast of a sailboat and keep it upright. It is designed to be strong and sturdy, providing a stable base for the sails to be raised and lowered. In contrast, running rigging is the system of ropes and lines that control the sails and other movable parts of the boat.

Standing rigging represents one of the core components of a sailboat ‘s design, providing the structural support necessary to keep the mast in place and ensure that the sails can be raised and lowered with ease. Made up of a variety of materials and components, standing rigging is a complex and sophisticated system that requires careful planning and maintenance to ensure optimal performance. Here are some of the types of standing rigging you might encounter:

- Wire Rigging Perhaps the most common type of standing rigging, wire rigging is made up of stainless steel or other metals that are twisted together to create cables of varying thickness. Wire rigging is relatively inexpensive and easy to maintain, but it can be prone to corrosion over time.

- Rod Rigging A popular option for high-performance sailboats, rod rigging is made up of thin, strong rods that are tensioned to provide support to the mast. Though relatively expensive, rod rigging is known for its durability and resistance to corrosion.

- Synthetic Rigging A newer development in the world of sailboat rigging, synthetic rigging uses high-tech fibers such as Dyneema or Spectra to create standing rigging that is strong, lightweight, and resistant to UV radiation and other environmental factors. Though still relatively expensive, synthetic rigging is gaining popularity due to its many advantages.

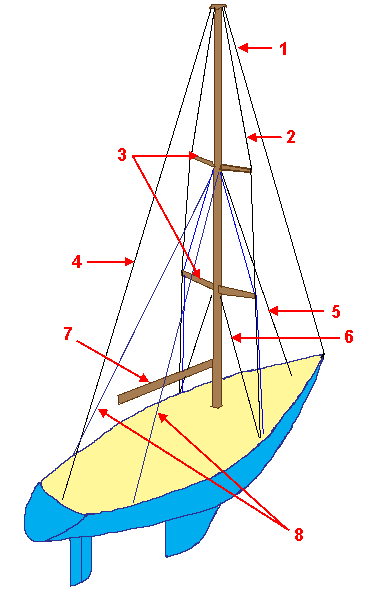

- (1) – Forestay The forestay is a wire or cable that runs from the top of the mast to the bow of the boat. It supports the mast from the front and helps to keep it from falling forward.

- (2) – Shrouds Shrouds are the wires or cables that run from the top of the mast to the sides of the boat. They provide lateral support to the mast and help to keep it upright.

- (3) – Spreaders Spreaders are the horizontal bars that extend from the mast and hold the shrouds away from the mast. They help to distribute the load from the sails and prevent the mast from collapsing.

- (4) – Backstay The backstay is a wire or cable that runs from the top of the mast to the stern of the boat. It supports the mast from the rear and helps to keep it from falling backwards.

- (5) – Inner forestay The inner forestay is a wire or cable that runs from the mast to the bow of the boat, inside the forestay. It provides additional support to the mast and is often used for heavier sails.

- (6) – Sidestay The sidestay is a wire or cable that runs from the mast to the side of the boat. It provides additional lateral support to the mast and helps to prevent it from swaying.

Running Rigging

Running rigging is the system of ropes and lines that control the sails, spars, and other movable parts of a sailboat. It is designed to be adjustable, allowing sailors to trim the sails to match the wind conditions and course of the boat. In contrast, standing rigging is the system of cables and wires that support the mast and keep it upright.

Running rigging is the unsung hero of sailboat design, providing the control and adjustability necessary to keep a boat moving smoothly through the water. Made up of a complex system of ropes, lines, and pulleys, running rigging is a crucial element in the art of sailing, allowing sailors to trim their sails to match the wind conditions and steer their boats with precision. Here are some of the key components of running rigging:

- Halyards These are the ropes that are used to raise and lower the sails. Depending on the size and type of boat, halyards may be made from synthetic fibers or more traditional materials such as hemp or nylon. (1) – Jib Halyard (2) – Main Halyard

- Sheets Sheets are the ropes that control the position of the sails relative to the wind. They are typically made from braided synthetic fibers or other high-strength materials and are adjusted using winches or cleats. (3) – Main Sheet (4) – Jib Sheet

- Blocks and Pulleys These small but essential components allow the ropes of the running rigging to move freely, reducing friction and making it easier to adjust the sails. They are often made from lightweight, high-strength materials such as aluminum or carbon fiber.

- Cleats Cleats are the small, wedge-shaped devices that are used to secure the running rigging in place. They are typically made from metal or synthetic materials and are designed to hold the ropes securely while still allowing for quick adjustments.

What are the signs of wear and tear in standing rigging?

Signs of wear and tear in standing rigging can include visible corrosion or rust on wire or rod rigging, fraying or unraveling of synthetic rigging, loose or damaged fittings, and any noticeable deformation or bending of the rigging components.

How often should I inspect and replace standing rigging?

The frequency of inspection and replacement for standing rigging depends on various factors, including the type of rigging material, the age of the rigging, and the manufacturer recommendations. As a general guideline, it is recommended to have a professional rigging inspection at least every 2-3 years.

Are there any regulations or standards for standing rigging?

Yes, there are industry standards and regulations for standing rigging. One widely recognized standard is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 12215-9, which provides guidelines for the design, construction, and testing of standing rigging on small craft. Additionally, various national and international sailing associations, such as the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) and the International Sailing Federation (ISAF), offer guidelines and recommendations for rigging standards.

What are the common causes of failure in standing rigging?

Common causes of failure in standing rigging can include fatigue from constant stress and loading, corrosion of metal rigging components, inadequate tensioning or adjustments, improper installation or maintenance, and damage from accidental impacts or mishandling.

How do I properly maintain and clean running rigging?

Proper maintenance and cleaning of running rigging involve regular inspection, washing, and lubrication. Inspect the ropes and lines for signs of wear, fraying, or damage, and replace any worn-out or damaged components. To clean synthetic ropes, rinse them with fresh water to remove salt and dirt, and use a mild soap if necessary. Avoid using harsh chemicals or bleach. Lubrication is essential for smooth operation, and you can apply a silicone-based or dry lubricant to the pulleys and blocks, following manufacturer recommendations.

Similar Posts

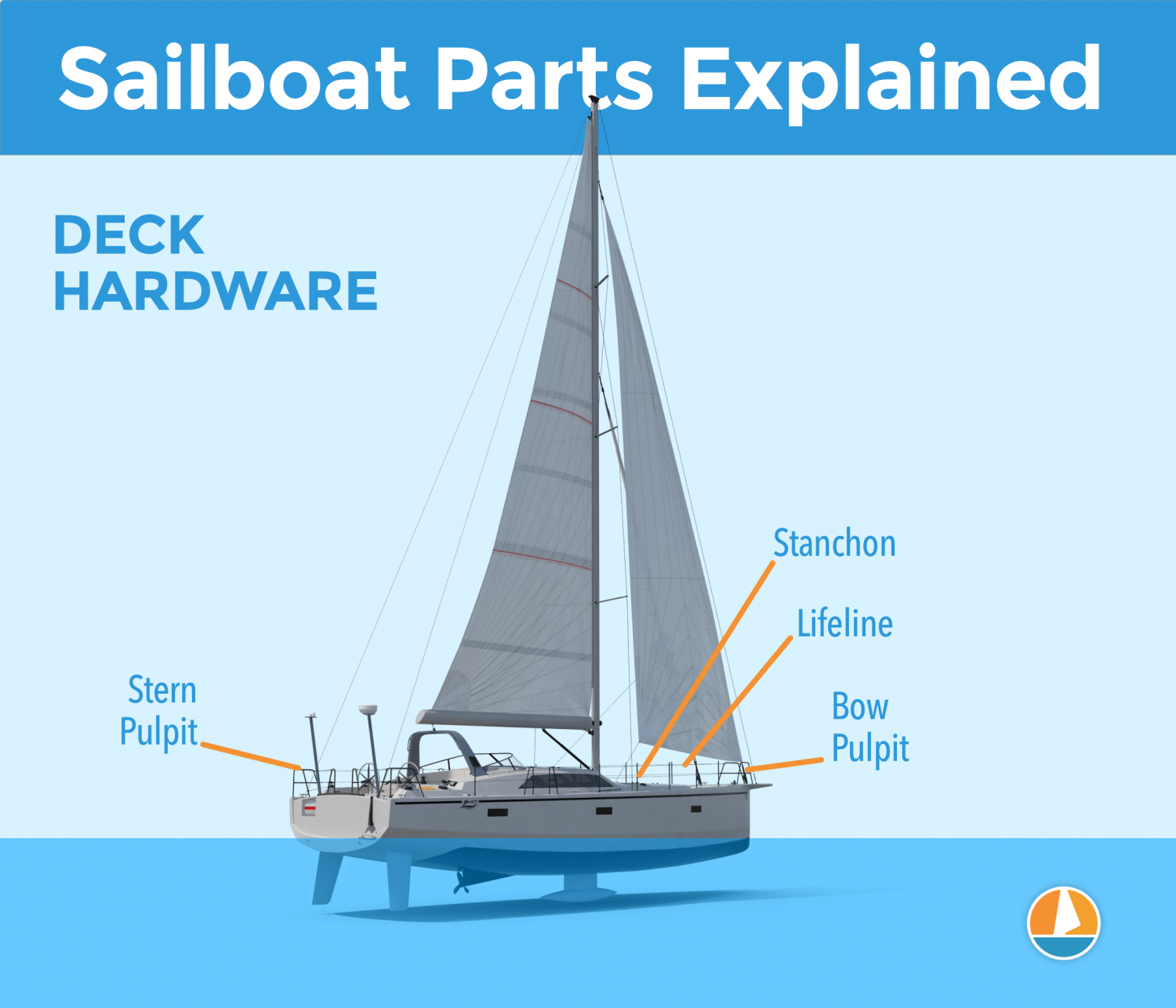

Basic Sailing Terminology: Sailboat Parts Explained

Sailing is a timeless activity that has captivated the hearts of adventurous souls for centuries. But, let’s face it, for beginners, sailing can be as intimidating as trying to navigate through a dark, labyrinthine maze with a blindfold on. The vast array of sailing terminology, sailboat parts and jargon can seem like a foreign language…

What is a Ketch Sailboat?

Ketch boats are frequently seen in certain regions and offer various advantages in terms of handling. However, what is a ketch and how does it stand out? A ketch is a sailboat with two masts. The mainmast is shorter than the mast on a sloop, and the mizzenmast aft is shorter than the mainmast. Ketches…

Advantages of Catamaran Sailboat Charter

A catamaran sailboat charter is an exciting way to explore the beauty of the sea. Whether you are an experienced sailor or a first-timer, booking a catamaran sailboat charter has a lot of advantages that you can enjoy. In this article, we will discuss the advantages of booking a catamaran sailboat charter, so that you…

Mainsail Furling Systems – Which one is right for you?

With the variety of options of mainsail furling systems available, including slab, in-boom, and in-mast systems, it can be challenging to determine which one best suits your needs. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the pros and cons of each system, enabling you to make an informed decision that aligns with your sailing requirements….

What is a Keel?: The Backbone of a Ship

As ships sail through tumultuous seas, their stability and maneuverability are tested to the fullest extent. The intricate design and engineering that go into a ship’s construction ensure that it can withstand the forces of nature and navigate through any challenging conditions. One of the most critical components of a ship’s design is the keel,…

Monohulls vs. Catamarans: Which One is Best for You?

If you’re considering purchasing a sailboat, you might be wondering which type of vessel is best suited for your seafaring adventures. Fear not, for we’re here to help you weigh the differences between monohulls vs. catamarans to make an informed decision. Now, before we dive into the nitty-gritty details of hull design, sail handling, and…

Parts of a Sailboat Rigging: A Comprehensive Guide

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 6, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer: Parts of a Sailboat Rigging

The sailboat rigging consists of various components essential for controlling and supporting the sails. Key parts include the mast, boom, shrouds, forestay, backstay, halyards, and sheets.

Understanding the Basics: A Comprehensive Overview of the Parts of a Sailboat Rigging

Title: Understanding the Basics: A Comprehensive Overview of the Parts of a Sailboat Rigging

Introduction: Sailboats have been a symbol of freedom and adventure for centuries. Whether you are an avid sailor or an aspiring skipper, understanding the various components that make up a sailboat rigging is essential. In this insightful guide, we will dive into the world of sailboat rigging, unraveling its intricacies while shedding light on its importance and functionality. So tighten your mainsails and let’s set sail on this knowledge-packed journey!

1. Mast: The mast is the vertical spar that supports the sails . It provides structural integrity to the entire rigging system and enables harnessing wind power effectively. Constructed from materials such as aluminum or carbon fiber, modern masts are designed to be lightweight yet robust enough to withstand varying weather conditions .

2. Standing Rigging: The standing rigging refers to all fixed parts that support the mast. This includes stays (fore, back, and jumper) which run between the masthead and various points on the hull or deck, like chainplates or tangs. Shrouds (cap shrouds, intermediate shrouds) help counteract lateral forces by providing lateral support to prevent excessive sideward movement of the mast.

3. Running Rigging: Unlike standing rigging, running rigging comprises lines that control sails’ deployment and trim dynamically during sailing maneuvers . The halyard raises or lowers a sail along its respective track within the mast groove while keeping it securely fastened in place when needed.

4. Sails: Of course, we can’t discuss sailboat rigging without mentioning sails themselves! They are like wings for your boat – converting wind energy into forward motion efficiently . Main sails typically attach through slides onto a mast track using luff cars for easy hoisting and lowering during different conditions.

5. Boom: The boom plays a crucial role in sail control , as it connects the aft end of the mainsail to the mast. By controlling the angle of the boom, sailors can adjust the shape and trim of the main sail for optimum performance against varying wind conditions.

6. Spreader: Spreader arms are horizontal poles extending from some point up the mast’s length. They serve two purposes: keeping shrouds apart to improve sail shape and reducing compressive loads on the rigging by forcing them away from each other.

7. Turnbuckles: Turnbuckles are adjustable devices used to tension standing rigging elements such as shrouds and stays. These fittings allow sailors to fine-tune rigging tensions while maximizing stability and overall performance based on prevailing weather conditions.

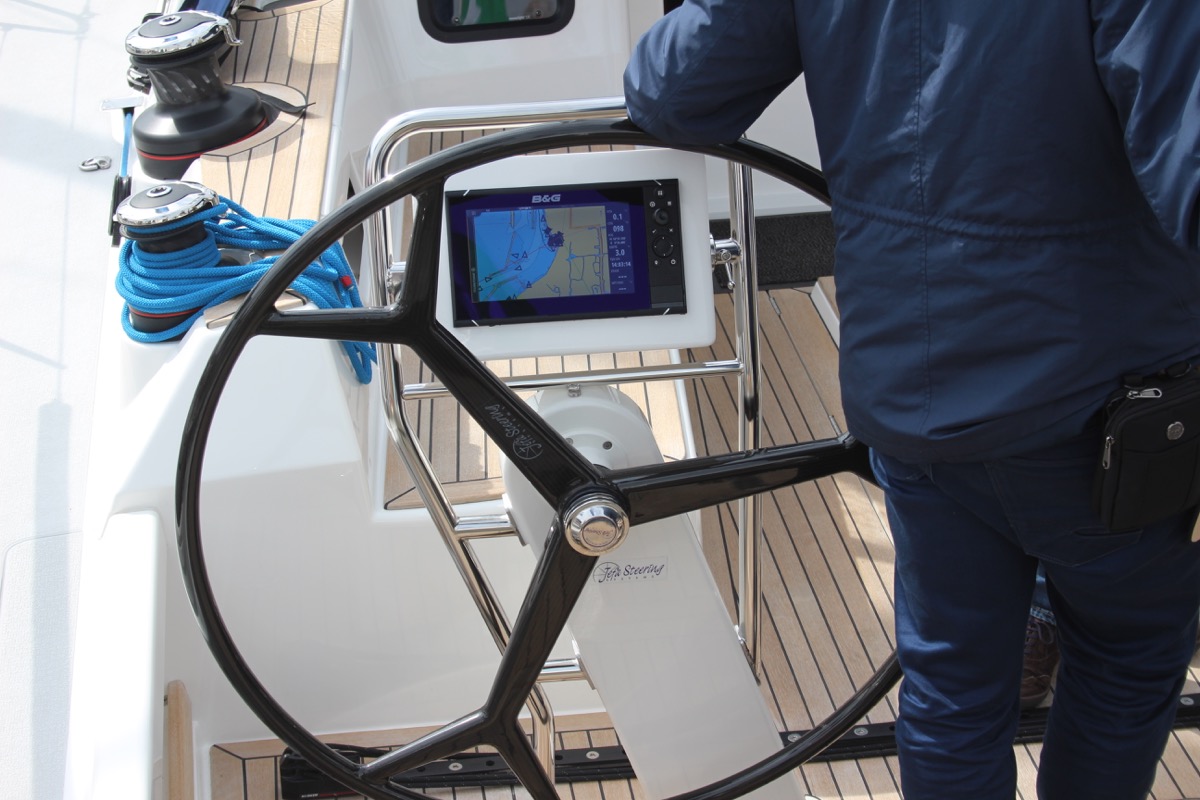

8. Winches: Winches are mechanical devices primarily used for easing or trimming running rigging lines under high loads. With a simple rotation, winches convert human effort into mechanical advantage, allowing efficient handling of lines for adjusting sails in different situations.

Conclusion: Understanding your sailboat rigging is not just essential for safe sailing but also for harnessing its maximum potential during every voyage. From deciphering various components like masts, standing and running rigging, booms, spreaders, turnbuckles, and winches – each element plays a crucial role in ensuring a smooth sailing experience. So next time you find yourself out on open waters, take a moment to appreciate these intricate systems that keep you powered by nothing but wind!

Step by Step Guide: How to Properly Assemble and Install the Various Parts of a Sailboat Rigging

Welcome fellow sailors and enthusiasts! Today, we are diving into the intricate world of sailboat rigging. Whether you are an experienced sailor or a newcomer to the sailing community, understanding how to properly assemble and install the various parts of a sailboat rig is essential for smooth and safe sailing. So, grab your tools and let’s get started on this step-by-step guide !

Step 1: Gather Your Tools and Materials Before embarking on this rigging journey, it’s crucial to have all your tools and materials ready. Here is a list of essentials you’ll need:

– Stainless steel wire rigging – Turnbuckles – Fittings and hardware such as clevis pins, shackles, and thimbles – Measuring tape or ruler – Wire cutters – Crimping tool or swaging machine (depending on your preference) – Electric drill (if required) – Lubricant or anti-seize compound

Make sure you have everything organized before starting. A well-prepared sailor is a successful one!

Step 2: Inspect Existing Rigging (If Applicable) If you own a used boat or are replacing old rigging, take some time to inspect the current setup. Look out for any signs of wear, frayed wires, or damaged fittings. It’s crucial to address these issues before proceeding with installation as they can compromise safety at sea.

Step 3: Measure Twice; Cut Once! Now that everything is set up let’s proceed by measuring the length needed for each piece of wire rigging carefully. Tinier inaccuracies in measurement during this step can lead to major inconveniences later.

Ensure you give yourself ample space for adjusting tension using turnbuckles. Pro-tip: It’s better to cut the wire slightly longer than needed rather than cutting it too short!

Step 4: Attach Fittings – The Devil Lies in Details Once you have measured and cut the rigging wire, let’s start attaching the fittings. This is where precision comes into play. Begin with inserting thimbles onto each end of the wires to avoid kinks or fraying. Next, connect the turnbuckles and fittings according to your sailboat’s specific rigging plan.

Step 5: Tension Matters Now that you have installed all the necessary fittings, it’s time to tension the rigging. This step requires a bit of finesse as over-tightening can damage equipment, while under-tightening can compromise performance.

Using a tension gauge, ensure that you achieve optimal tension on all parts of your sailboat’s rigging. It might take some trial and error, but finding that sweet spot is worth it!

Step 6: Inspect and Lubricate Before setting sail , always double-check everything! Look for any loose fittings or signs of wear once again. You wouldn’t want to go through these steps all over again out in the middle of nowhere!

Additionally, apply lubricant or anti-seize compound to prevent corrosion and ensure smooth operation of turnbuckles and other moving parts.

And there you have it – a professionally and properly assembled sailboat rigging! Sit back for a minute or two to appreciate your workmanship before feeling that excitement rush through as you’ll soon set sail smoothly onto those horizon-stretching waters.

Remember, practice makes perfect when it comes to mastering this skill. Over time, you’ll develop your own techniques and become a maestro at sailboat rigging assembly. Happy sailing!

Top Frequently Asked Questions about Sailboat Rigging Components Answered

Are you new to sailing or considering purchasing a sailboat? No matter your experience level, understanding the rigging components of a sailboat is crucial for safe and successful navigation on the water. In this blog post, we aim to answer some of the top frequently asked questions about sailboat rigging components. So, let’s dive in!

1. What are sailboat rigging components? Sailboat rigging components refer to the various parts and systems that help support and control the sails on a sailboat. These components include standing rigging (the fixed parts) and running rigging (lines that can be adjusted). Some common examples of rigging components are the mast, boom, shrouds, stays, halyards, sheets, and blocks.

2. What is the purpose of each rigging component? Each component serves a specific purpose in sailing . The mast supports the sails and provides leverage for controlling their shape. The boom holds down the bottom of the mainsail and allows adjustment for different points of sail . Shrouds provide lateral support to prevent excessive side-to-side movement of the mast. Stays offer fore-and-aft support to keep the mast from leaning too far forward or backward. Halyards raise and lower sails while sheets control their angle in relation to wind direction.

3. How often should I inspect my sailboat’s rigging ? Regular inspection is crucial for ensuring your safety on the water . We recommend conducting visual inspections before every sailing trip and more thorough inspections at least once a year or per manufacturer recommendations. Look out for any signs of wear, corrosion, loose fittings, or frayed lines that may indicate potential issues.

4. Can I replace my own rigging components? While minor repairs or adjustments can typically be done by boat owners with some knowledge and experience, replacing major rigging components should ideally be done by professionals who specialize in sailboat rigging services. They have the expertise and equipment necessary to properly install and tension components, ensuring your safety.

5. How long do sailboat rigging components typically last? The lifespan of rigging components depends on various factors such as usage, maintenance, and exposure to environmental conditions. Stainless steel stays can last for 10-15 years or longer with regular inspections and maintenance, while synthetic running rigging (such as ropes made from high-performance fibers) may have a shorter lifespan of 3-5 years.

6. Are there any safety tips related to sailboat rigging? Absolutely! Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment when working with or near rigging components. Take care not to overload or overstress the rig by correctly tensioning lines within manufacturer specifications . Avoid standing under or in close proximity to the mast while raising or lowering it, as it can be dangerous if it accidentally drops.

7. What are some common signs of rigging failure? Rigging failures can be catastrophic, so being able to identify potential issues is vital. Look out for visible cracks, rust, elongation, broken strands on wires, loose fittings, excessive wear on ropes, or unusual noises while sailing. Any of these signs should prompt an immediate inspection and possible replacement of affected components.

In conclusion, understanding sailboat rigging components is crucial for any sailor looking to navigate safely on the water. By familiarizing yourself with these frequently asked questions and following proper inspection and maintenance practices, you’ll enjoy a smooth sailing experience while prioritizing your safety at all times!

Exploring the Essential Components: An In-Depth Look at Key Parts of a Sailboat Rigging

Sailing is a thrilling and age-old activity that has fascinated adventurers and seafarers for centuries. At the heart of every sailing vessel lies its rigging, which is a complex system of ropes, wires, and equipment that hold the sails in place and allows for precise control over the boat’s movement. In this blog post, we will take an in-depth look at the key components of a sailboat rigging to understand their importance and how they contribute to the overall sailing experience.

Mast: The backbone of any sailboat rigging is its mast. This tall vertical structure supports the sails and provides stability to the vessel . Made from materials such as aluminum or carbon fiber, masts are designed to withstand strong winds and carry considerable loads. They come in various shapes and sizes depending on the type of boat and intended use.

Boom: Attached horizontally towards the bottom of the mast, the boom serves as a critical component in controlling the position of the mainsail – typically the largest sail on board. Acting as an extension of the mast, it allows for adjustments in sail trim by pivoting up or down.

Shrouds: These sturdy wire cables are attached to either side of the mast at multiple levels, forming a crucial part of sailboat rigging’s structural integrity. Shrouds keep the mast upright by counteracting lateral forces created by wind pressure on sails . Adjustable tensioning systems enable sailors to fine-tune shroud tension according to prevailing conditions.

Stay: Similar to shrouds but located further forward on most boats, stays provide additional support for maintaining mast stability. Fore-stay runs from top-to-bow while back-stays run from top-to-aft; together they prevent excessive forward or aft bending movements during intense wind pressures.

Turnbuckles: Within sailboat rigging systems lie turnbuckles – mechanical devices used for adjusting tension in wires or ropes like shrouds or stays. These clever devices simplify the task of tightening or loosening rigging components, enabling sailors to optimize sail shape and boat performance with ease.

Halyards: Essential for hoisting sails up and down, halyards are ropes used to control the vertical movement of the sails . They are typically operated through winches, which increase mechanical advantage and make raising and lowering large sails manageable.

Blocks: Also known as pulleys, these simple yet crucial devices help redirect the path of ropes within a sailboat rigging system. Blocks increase mechanical advantage by changing the direction of applied force, making it easier for sailors to control different aspects such as sail trim or adjusting tension.

Running Rigging vs Standing Rigging: Sailboat rigging can be classified into two main categories – running rigging and standing rigging. Running rigging refers to all movable lines and ropes that control sail position, while standing rigging encompasses all stationary components that give structure to the mast. Both elements work in harmony to ensure efficient maneuverability and safety at sea .

Understanding these key components within a sailboat’s rigging is essential for any aspiring sailor or seasoned mariner alike. It not only allows them to appreciate how these intricately designed systems function together but also helps enhance their sailing skills by leveraging each component’s unique role.

So next time you set foot on a sailboat or watch one glide gracefully across the water, take a moment to admire the finely tuned rigging – a mesmerizing web of interconnected parts that enable humans to harness the power of wind and embark on unforgettable nautical adventures.

The Crucial Role of Each Part: Unveiling the Functionality and Importance of Sailboat Rigging Components

Sailboat rigging components may seem simple and insignificant at first glance, but anyone who has sailed knows just how crucial each part is to the overall functionality and performance of a sailboat. From the mast to the shrouds, every component plays a vital role in ensuring safe navigation, efficient sailing, and maximum performance on the water.

One of the most essential parts of any sailboat rigging system is the mast. Serving as the backbone of the entire structure, the mast provides vertical stability and supports various sails that catch the wind . The mast’s height and shape significantly impact a boat’s performance, affecting not only its speed but also its ability to handle different wind conditions. A sturdy mast ensures that forces are properly distributed throughout the rigging system, preventing excessive strain or potential failure.

Connected to both sides of the mast are what are known as shrouds. These cables or wires act as primary support structures for restraining lateral movement and maintaining balance in heavy winds. Shrouds come in different sizes and tensions depending on factors such as sail size and boat length. Proper tensioning of shrouds is crucial for maintaining structural integrity and minimizing flexing under intense force.

Another integral part is the forestay – a cable or wire running from near or at the top of the mast down to the bow area of a sailboat . The forestay supports forward strength and controls stay sag- an essential factor for optimizing aerodynamics by shaping how sails interact with wind. It helps maintain proper sail geometry while limiting unnecessary heel (leaning) during maneuvers or gusts.

The backstay is another component critical for stability and control. Running from either side of the stern up to near or at the top of the mast, it helps counterbalance fore-aft bending forces created by wind pressure against a boat’s sails pushing it forward. By adjusting backstay tension, sailors can fine-tune their boat’s responsiveness to changes in wind speed or balance.

The boom, a horizontal spar attached to the mast, plays a crucial role in controlling the angle and shape of the mainsail. It acts as a pivot point for adjusting sail trim, allowing sailors to maximize lift and minimize drag based on wind conditions. With its connection to the gooseneck at the foot of the mast, it enables easy raising and lowering of the mainsail for quick adjustments or docking maneuvers .

Moreover, various blocks and pulleys are scattered throughout a sailboat’s rigging system playing essential roles in creating mechanical advantages. These components reduce friction and redirect forces generated by sails and lines during sailing operations, making it easier for sailors to handle heavy loads while preserving their energy. Choosing high-quality blocks with low-friction bearings is crucial for efficient sail handling while maintaining control.

Understanding how each part functions individually is significant; but more importantly, appreciating how they work in harmony is where true seamanship resides. Rigging components must be designed and maintained carefully to ensure safety, performance, and optimal functionality on any sailing adventure.

In conclusion, sailboat rigging components may appear simple to some extent but hold tremendous importance in enhancing a boat’s capabilities on water. From providing vertical stability with masts and dampening lateral movement with shrouds to shaping sails’ interaction with wind using forestays and backstays – every component has a crucial role to play. Understanding how these parts function individually and collectively helps sailors navigate safely while maximizing performance out on the open sea

Troubleshooting Tips: Common Issues and Solutions related to different parts of a sailboat rigging

Introduction: The rigging of a sailboat is an essential component that allows for safe navigation and optimal performance on the water. However, like any mechanical system, it can experience issues from time to time. In this blog post, we will provide detailed professional troubleshooting tips for common problems related to various parts of a sailboat rigging. Whether you’re an experienced sailor or just starting out, these solutions will help keep your rigging in top shape and ensure smooth sailing on every adventure.

1. Mast and Standing Rigging: One common issue sailors face is the presence of squeaking noises coming from the mast or standing rigging while underway. This can be quite bothersome and distracting during a peaceful sail. To resolve this problem, start by checking the connections between different components of the rigging and tighten any loose fittings appropriately. Additionally, using lubricants specifically designed for marine environments can significantly reduce friction between movable parts, eliminating annoying creaks and groans as you ride the waves.

2. Shrouds and Forestay: Another issue frequently encountered involves misaligned shrouds or forestay tension that affects the overall stability of the mast. If you notice your mast leaning slightly to one side or backward, it’s likely due to incorrectly adjusted shrouds or an improperly tensioned forestay. To rectify this, use a tension gauge to ensure consistent tension across all shrouds while avoiding excessive strain on either side of the mast base. By maintaining proper alignment and equal tension distribution, your rigging will provide maximum support when experiencing strong winds or rough conditions.

3. Running Rigging (Lines): Running rigging encompasses all lines used for controlling sails such as halyards, sheets, and control lines – crucial elements for proper sail handling. A typical problem associated with running rigging is line chafing caused by repeated friction against sharp edges or abrasive surfaces onboard. Inspect your lines regularly for signs of wear, paying close attention to areas exposed to constant rubbing. To prevent chafing, secure protective coverings or install specialized guards where necessary. Regularly washing and lubricating your lines will also extend their lifespan and ensure smooth operation.

4. Block and Tackle Systems: Block and tackle systems play a vital role in distributing loads and facilitating the movement of sails, particularly in larger sailboats. A common issue arises when blocks become jammed or fail to rotate freely due to debris buildup or lack of proper maintenance. To address this problem, inspect all blocks systematically, disassembling them if required, and clean out any accumulated dirt or salt crystals thoroughly. After cleaning, applying a liberal amount of marine-grade grease will promote smooth rotation and reduce the likelihood of future blockages.

Conclusion: Effective troubleshooting is essential for maintaining a sailboat rigging system that performs optimally and ensures a safe experience on the water. By following these detailed professional tips, you can address common issues associated with different parts of your sailboat rigging promptly and efficiently. Remember to conduct regular inspections, prioritize preventive maintenance, and seek professional assistance whenever needed. With a well-maintained rigging system at your disposal, you can embark on each sailing journey confidently, knowing that you’re prepared to overcome any challenges that may arise along the way.

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

Better Sailing

What is Sailboat Rigging?